Archive for the ‘cryopreservation’ Category

The Embryo Bank Dilemma: Reviewing the Issues, Historical Perspectives and Offering Potential Solutions

Craig R. Sweet, M.D

Reproductive Endocrinologist

Practice and Medical Director

Embryo Donation International

Introduction

In my last blog, “Why Creating ‘McEmbryos’ is Just Plain Wrong,” I wrote about my concerns regarding the creation of an embryo bank at a California clinic. In this follow-up segment, I want to re-state the issues, discuss the past history of embryo banking in the U.S., provide a list of recently written thoughtful blogs on the topic, offer possible solutions to the dilemma and discuss where we should go from here.

A “Reader’s Digest” version

California Conceptions (CC), as outlined in Alan Zarembo’s L.A. Times article apparently combined donor eggs with donor sperm and divided the resulting embryos among a number of embryo recipients. This process is commonly called a “split or shared donor/donor cycle” but was called “embryo donation” by CC. Any embryos remaining, after the recipients received their allotment, would be cryopreserved and owned by CC.

The road was paved with good intentions

I feel that CC was really trying to offer a cost-affective alternative for patients and that its true intent was to keep the size of its embryo bank as small as possible. Even with good intentions, however, it is quite likely that the embryo bank will grow. In addition, to sanction the creation of a small embryo bank will almost certainly result in the creation of larger embryo banks across the country. These banked embryos for commercial use are what I called “McEmbryos.” There also needs to be a clear distinction between embryo banking for commercial use and the process of banking one’s own embryos (i.e., collecting through multiple IVF retrievals) to be used by individuals to build their families in the future.

I still have three main concerns:

- I do not feel that embryo banks are appropriate and could result in a plethora of unintended consequences.

- I feel that corporations, businesses or physician practices should not own embryos.

- Lastly, the process of a “split or shared donor/donor cycle” should be called “embryo creation” or, at the very least, not called embryo donation.

This has happened before

An article by Gina Kolata in the New York Times in 1997 revealed that “ready-made embryos” were already being made for “adoption.” Columbia-Presbyterian and Reproductive Biology Associates were named in the article as providing “premade” embryos to patients. According to the article, most of the embryos were created when donor egg recipients backed out of the process, but the egg donors still underwent the egg retrieval; their subsequent retrieved donor oocytes were combined with donor sperm. Lori B. Andrews, a professor of law at Chicago-Kent College of Law, was quoted as having concerns about the supermarket approach to embryos while the clinicians thought it wasteful to not retrieve and fertilize the donor oocytes if the egg donors were ready for the retrieval.

In 2007, Center for Genetics and Society Senior Fellow and UC Hastings Law Professor Osagie Obasogie wrote an op-ed for the Boston Globe about a Texas center that had created an embryo bank. He was concerned about the “Wal-Martization” of human embryos, a phrase similar to my “McEmbryos.”

In November of 2012, in response to the N.Y. Times article, Jessica Cussins of the Center for Genetics and Society wrote an excellent blog on the topic, also following-up on the 2007 article by Professor Obasogie. The Texas center was eventually closed and was the subject of an FDA investigation, which eventually found that the creation of an embryo bank did not fall under FDA jurisdiction. John Robertson, Esq., wrote an excellent commentary on the topic in the Bioethics Forum in that same year.

Embryo banks have come and gone, garnering media attention and criticism and I believe it is finally time to set some ethical standards of care about them.

How New York decided to handle the embryo bank issue

Almost five years ago, the state of New York issued regulations for tissue banks and nontransplant anatomic banks, addressing the potential of creating embryo banks:

Almost five years ago, the state of New York issued regulations for tissue banks and nontransplant anatomic banks, addressing the potential of creating embryo banks:

Embryos shall not be created for donation by fertilizing donor oocytes with donor semen, except at the request of a specific patient who intends to use such embryos for her own treatment. [NYS 52-8.7(h)]

Embryos were not to be created to store in embryo banks but only created at the behest of a specific patient and subsequently owned by that patient. Simply modifying the statement above to include “… such embryos for his/her own treatment,” would address the issue adequately, with the sentence potentially used by various organizations as they hopefully set ethical standards of care.

Potential consequences to the creation of an embryo bank

I have been called an alarmist by some for bringing up what I feel are the following potential dangers of having embryos banks in the U.S:

- If a small embryo bank is allowed to flourish, then large embryo banks will most certainly follow.

- Poorly designed and reactive legislation may be created on the state or national level as there may be further calls to regulate what are perceived to be “unregulated IVF facilities.”

- “Personhood” advocates may become further emboldened to win personhood for the embryos to protect them from becoming “McEmbryos.”

I don’t think these unintended consequences are that farfetched and need to be considered carefully should embryo banks continue unchecked.

My reluctant decision to come forward

About the last thing I wanted to do was to comment on another reproductive endocrine practice comprised of caring staff members dedicated to the care of their patients. I have been criticized for taking such a stand and accused of doing this purely for competitive reasons. In reality, I have been working with the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s (ASRM) and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies, (SART) since October of 2011, trying to elicit a set of guidelines prior to the writing of my blog. I far preferred to stay out of the limelight and let the “powers-that-be” decide what should be done next. When the L.A. Times article was published, it de-emphasized the ethical issues and potential unintended consequences of the CC embryo banking practice, so I felt I had no choice but to bring the topic up front and center.

About the last thing I wanted to do was to comment on another reproductive endocrine practice comprised of caring staff members dedicated to the care of their patients. I have been criticized for taking such a stand and accused of doing this purely for competitive reasons. In reality, I have been working with the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s (ASRM) and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies, (SART) since October of 2011, trying to elicit a set of guidelines prior to the writing of my blog. I far preferred to stay out of the limelight and let the “powers-that-be” decide what should be done next. When the L.A. Times article was published, it de-emphasized the ethical issues and potential unintended consequences of the CC embryo banking practice, so I felt I had no choice but to bring the topic up front and center.

Others responded to the discussion

Several other infertility professionals discussed the ethical issue in articles or blogs in the weeks following the L.A. Times piece. Excluding those that simply summarized the situation, I listed below what I think are some of the better blogs:

Supporting embryo banking

- Marni Soupcoff, Esq., “Marni Soupcoff on the sale of fertilized embryos: How much for the blastocyst in the window?”

Neutral to embryo banking

- Julie Shapiro, Esq., “Custom Made or Off The Rack?”

- Carole C. Wegner, Ph.D., “Embryos for Donation: Where are the ethical boundaries?“

- Elizabeth Swire Falker, Esq., “The Bizarre World of Embryo Banking. Where My Motherhood and Morality Meet”

Against embryo banking

- Andrew Vorzimer, Esq., “Get Pregnant With Built On Spec Embryos Or Get Your Money Back!”

- Jessica Cussins, B.A., “Embryos for Sale: ‘When You Want Them, How You Want Them, or Your Money Back”

- Sara R. Cohen, LL.B., “It’s not about the Money: Why we are So Concerned about a California IVF Clinic’s Anonymous Embryo Program”

- Mikki Morrissette, “Creating Embryos To Sell“

My thanks to all of the authors for taking the time to discuss the issue in an open forum.

Proposed remedies to the current dilemma

From the beginning, I have been offering remedies to the embryo bank dilemma. Although far be it from me to tell CC how to run its business, these are a few ideas I had to offer:

Only patients should own embryos-

No organization, corporation or physician practice should own embryos except in the most extreme circumstances, such as embryo abandonment. With embryo donation, it is most appropriate that the donor facility simply holds the embryos, with the donors still being able to request the return of their embryos, up to the point of transfer into the recipients, should a catastrophic occurrence take place, Attorneys refer to this as being a guardian, a conservator, or a temporary holder of goods. When presenting at the American Bar Association Family Law Section Spring conference in April of 2012, many of the attorneys there strongly supported the concept of conservatorship of the donated embryos over facility ownership.

If the embryos are returned to the donor, it seems appropriate to ask the donors to reimburse the embryo donation facility for all reasonable fees expended in originally obtaining the donated embryos and returning them to the donors. We have been running our embryo donation program this way for over 12 years and we encourage others to do the same.

Excess cryopreserved embryos could be owned by patients-

As best as I can surmise for CC, their business model is to recruit a number of embryo recipients and then transfer 1-2 donor/donor embryos into each recipient. I suggest that any remaining embryos be owned by one or more of the recipients and the entire cycle should not move forward until at least one patient agrees to take the extra cryopreserved embryos, should any exist. Extra charges could be levied to those that secure the remaining embryos. In this way, no embryos remain to create an embryo bank and the CC business model remains essentially intact.

Renaming the process-

The combination of donor sperm with donor eggs and then calling them donated embryos does not fit with the ASRM definition of embryo donation (Ethics Committee of the ASRM, 2009). Embryo creation is a far better term or “shared or split donor/donor cycle” is perhaps even more appropriate. Calling such embryos donated embryos debases the amazing gift that embryo donors provide when donating their embryos.

Who should set the standards?

SART has reviewed the concerns stated in my previous blog but I don’t think it yet has arrived at a

SART has reviewed the concerns stated in my previous blog but I don’t think it yet has arrived at a

conclusion. My understanding is that the ASRM Ethics Committee is to take up the topic during the early months of 2013. As our main guiding societies, I believe they need to take the lead, develop position statements and provide ethical standard of care guidelines for all practices to use.

Once ASRM and SART have provided ethical standard of care guidelines, I will next request that the

Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society and the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (I am a member of both) consider the topic and respond with their own recommendations if they see fit.

It is not out of the realm of possibility that numerous societies could collaborate to form a consensus, such as they did when they banned the support and publication of human reproductive cloning research.

Summary comments

So where are we now on this dilemma? SART has discussed the topic but summary statements are pending. The ASRM Ethics Committee will soon meet, with the embryo bank topic apparently on the agenda. Assuming the Ethics Committee feels the topic has merit, I am uncertain how long it will take for them to release a position statement. I am hopeful that “the powers that be” will be attentive in finding a compromise that will allow CC to continue to offer their skilled reproductive services while preventing the formation of an embryo bank, no matter the size, further clarifying who should own embryos as well as the definition of embryo donation as it pertains to the current situation.

I don’t know about you but I don’t really like the idea of “McEmbryos,” or the commodification and “Wal-Martization” of human embryos. Patients should own them and decide their destiny. I am hopeful that our guiding societies will do just that – guide us on this sensitive and important topic.

Special thanks:

Thanks to Grace Centola, Ph.D., for helping to find the New York State statutes pertaining to embryo banking.

Thank you to Jessica Cussins for her blog on the topic, the reference by Professor Obasogie and her followup on the now closed Abraham Center for Life.

References:

Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. American Society for Reproductive Medicine: defining embryo donation. Fertil Steril. 2009 Dec;92(6):1818-9

.

What Impacts Embryo Donation Success Rates?

Craig R. Sweet, M.D.

Reproductive Endocrinologist

Corey Burke, B.S., C.L.S.

Laboratory Supervisor

Introduction

Asking what determines the success rates in embryo donation is an excellent question. The answer, as one might expect, is neither simple nor completely understood.

Embryologists and physicians try to choose the fewest number of healthy embryos for fresh transfers to increase success rates while minimizing multiple pregnancy rates. It is indeed a delicate balance. For example, it is well understood that in Europe, physicians transfer fewer embryos but patients also suffer significantly lower success rates than in North America. (Boostanfar R, et al. Fertil Steril 2012)

What variables do we examine to estimate probable success?

Since donated embryos are cryopreserved, the variables become even more complex compared to fresh embryos. In combining a great deal of published data and over 20 years of IVF and embryo transfer experience, we came up with what we feel are the variables which seem to influence success rates:

| Very Important! |

Preferred |

Less Optimal |

| Did the fresh cycle in which the embryos were frozen result in a pregnancy & delivery? |

Successful pregnancy and delivery |

Fresh transfer resulted in miscarriage or no pregnancy |

| Number of embryos available in a given donated set |

Four or more |

Three or fewer |

| Past implantation rates of both fresh and frozen embryo transfers |

High implantation rates |

Low implantation rates |

| Quality of the embryos frozen (link) |

High quality (Blastocyst) |

Medium quality |

| Age of the women when the eggs were provided to create embryos |

Less than 35 years old |

35 years of age or older |

| Overall health of the embryo recipient (link) |

Healthy |

With treated or untreated medical issues |

| Important |

Preferred |

Less Optimal |

| Stage of growth when the embryos were frozen (link) |

Day 5, blastocyst stage |

Day 3, 8-cell stage |

| Technique used to freeze/thaw or vitrify/warm the embryos (link) |

Vitrification |

Slow freeze |

| Overall frozen embryo transfer pregnancy rates for facility freezing the embryos |

30% or more |

Less than 30% |

| Overall frozen embryo transfer pregnancy rates for facility thawing the embryos (EDI) |

High at 30% or more |

Less than 30% |

| Ejaculated vs. surgically aspirated sperm used for fertilization |

Ejaculated sperm |

Surgically aspiration sperm |

| Somewhat Important |

Preferred |

Less Optimal |

| Was preimplantation genetic testing of the embryos done? |

Yes |

No |

| Age of the male producing the sperm |

Less than 40 years old |

More than 40 years old |

| Past successful deliveries with other embryos from donating facility |

Yes, with past deliveries |

Miscarriage, reduced survival of embryos or failed implantation |

| Probably Unimportant |

Preferred? |

Less Optimal? |

| Cryopreservation duration |

Less than 10 years? |

More than 10 years? |

The above variables influence EDI’s decision to both accept embryos from other facilities as well as determine how many donated embryos should be thawed/warmed to achieve a successful delivery.

The importance of the embryo recipient’s health should not be underestimated

In a previous blog, we described how important it was for our embryo recipients to be healthy. (link) Inadequately treated health problems, harmful medications, recreational drug use as well as smoking and weight concerns all play a potential role affecting success rates. It is clear that success depends on both the quality of the donated embryos and the overall health of the recipient.

Are all donating IVF facilities the same?

We understand that not all IVF facilities have the same success rates. Some facilities will have provided EDI  donated embryos with consistently high implantation rates while others may provide embryos of consistently lessor quality. EDI examines a facility’s past fresh and frozen embryo transfer pregnancy rates as well as its past history of providing EDI with donated embryos. It does, however, take a fair amount of time to seemingly identify a trend but we endeavor to examine all the variables we can. Our contact management database system was recently upgraded to track these variables more consistently.

donated embryos with consistently high implantation rates while others may provide embryos of consistently lessor quality. EDI examines a facility’s past fresh and frozen embryo transfer pregnancy rates as well as its past history of providing EDI with donated embryos. It does, however, take a fair amount of time to seemingly identify a trend but we endeavor to examine all the variables we can. Our contact management database system was recently upgraded to track these variables more consistently.

Do your embryos make the grade?

Understanding that all of the above variables are quite complex, we endeavored to find a simple way to convert the data into something patients could more easily understand. Since nearly all patients understand the basic A, B & C grades we used to receive in school, we modeled our grading of the embryos around these letter grades.

We created a mathematical model to assess a number of the above variables, converting the final analysis to A+, A, A-, B+, B and B- letter grades. Interestingly, we found the model really did help to predict delivery rates and continue to use it to this day to grade individual embryos as well as entire sets of donated embryos.

What information do we gain on the day of thaw and embryo transfer?

Most frequently, the embryos are thawed just hours before transfer. At times, we may thaw them days prior if, for example, they were frozen early in their development and we want to grow them further before deciding how many to transfer. Therefore, the following last set of variables will also influence success rates:

| Important |

Preferred |

Less Optimal |

| Survival rates of thawed embryos |

100% |

Less than 100% |

| Overall appearance of the thawed embryos |

Healthy, expanding and growing |

Evidence of cellular damage |

If 100% of the embryos, perhaps three out of three, survive the thaw and look healthy, we feel this is a good sign. If only 50% survive, for example perhaps only two of four, then we are concerned that the overall implantation rates will be reduced and that we might need to find more embryos to transfer just to get to the “finish line” of pregnancy and delivery. Ultimately, we want at least two high-quality embryos or up to four less certain quality embryos placed on the day of transfer.

What are the national success frozen embryo transfer delivery rates?

In 2009, the CDC reported that there were 26,069 frozen embryo transfers performed in the U.S. with an average delivery rate of 31% per embryo transfer procedure. In addition, there were 6,074 frozen embryo transfers using embryos created from donated eggs (i.e., younger women) with slightly higher delivery rates of 34%. Please recall that donated embryos generally come from the very same types of patients listed in these success rates.

In 2009, the CDC reported that there were 26,069 frozen embryo transfers performed in the U.S. with an average delivery rate of 31% per embryo transfer procedure. In addition, there were 6,074 frozen embryo transfers using embryos created from donated eggs (i.e., younger women) with slightly higher delivery rates of 34%. Please recall that donated embryos generally come from the very same types of patients listed in these success rates.

What are EDI’s success rates?

We do our best to screen the embryos, carefully trying to choose the embryos most likely to implant. We estimate delivery rates with donated embryos to range from 27 – 42%, depending on the many variables listed in this blog, with a multiple pregnancy rates of 20-25%. We wish the success rates were higher, but please understand that frozen/thawed embryos implant and grow less frequently than fresh embryos and these percentages are entirely consistent with the frozen embryo transfer success rates described in 2009, which ranged from 31-34%.

Even with the slightly lower delivery rates compared to fresh embryo transfers, embryo donation remains one of the best and most cost-effective options for patients who cannot otherwise afford egg donation or qualify for adoption. Embryo donation still allows a woman to experience pregnancy and delivery while bonding, nurturing and protecting the ongoing gestation.

Summary

There are many variables that go into determining the potential success rates for a given set of donated embryos. First, we attempt to examine these variables carefully in deciding if EDI will accept the donated embryos. Second, we use this same information to determine how many embryos we should thaw/warm and eventually transfer. The process remains a bit of an ART (pun intended) since the complete understanding of how all of these variables influence each other and the ultimate success rates are yet to be fully known.

References

“Annual ART Success Rates.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Reproductive Health, 19 Apr. 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://www.cdc.gov/art/ARTReports.htm>.

Boostanfar R, Mannaerts B, Pang S, Fernandez-Sanchez M, Witjes H, Devroey P; Engage Investigators. A comparison of live birth rates and cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates between Europe and North America after ovarian stimulation with corifollitropin alfa or recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone. Fertil Steril. 2012 Mar 27.

Reasons to Donate

By: Vicki D., an embryo donor

“In the order of nature we cannot render benefits to those from whom we receive them, or only seldom. But the benefit we receive must be rendered again, line for line, deed for deed, cent for cent, to somebody.’ – Ralph Waldo Emerson, Compensation

On May 13, 2010, I made a decision. It wasn’t your normal everyday decision on things like what shoes to wear, where to have lunch, or which shade of lipstick to buy. It even surpassed those important decisions we encounter in life such as what house to buy, the most lucrative financial investments and selecting the best care for elderly parents. It was a decision much more substantial, incredibly emotional and most importantly, everlasting. It was regarding the fate of our embryos. Yes; five embryos, frozen, suspended in time – a significant and extraordinary reminder of a successful IVF cycle producing twin girls just two years prior. Considering that my family was now complete, the desire to have more children had abated. But the process was far from over and I knew this going in. There are five potential lives to consider currently residing in a sub-zero environment. So the question remained… what did one do with extra embryos when one’s need or desire to expand your family has subsided?

In my quest to determine the future of my five frozen embryos, I discovered several options to choose from. These ranged from permanent storage – or in some cases “abandonment,” destruction, donation to stem-cell research,  donation to the IVF clinic lab, or donation to an infertile couple or person in need. Continued voluntary storage brought unnecessary substantial fees, not to mention the inevitable procrastination of decision making. Abandonment wasn’t an option for obvious reasons as I felt a responsibility towards these embryos. The only things I have ever abandoned in my life were the occasional art project or my first premature marriage in my early twenties. The concept of destruction simply didn’t make logical sense. Why go through all the expense and trouble of creating embryos that one day would be destroyed because there was no better option considered? Stem-cell research or IVF clinic donation seemed like fair choices since I wouldn’t have my twins without past research in IVF. Even so, there had to be a better option available that would help promote the preservation of life and help out infertile couples desperately wanting a baby.

donation to the IVF clinic lab, or donation to an infertile couple or person in need. Continued voluntary storage brought unnecessary substantial fees, not to mention the inevitable procrastination of decision making. Abandonment wasn’t an option for obvious reasons as I felt a responsibility towards these embryos. The only things I have ever abandoned in my life were the occasional art project or my first premature marriage in my early twenties. The concept of destruction simply didn’t make logical sense. Why go through all the expense and trouble of creating embryos that one day would be destroyed because there was no better option considered? Stem-cell research or IVF clinic donation seemed like fair choices since I wouldn’t have my twins without past research in IVF. Even so, there had to be a better option available that would help promote the preservation of life and help out infertile couples desperately wanting a baby.

I remember the years of anguish I experienced being infertile. Everywhere I went I saw pregnant women or newborn babies. It became an obsession, perceived as something so intangible for me yet came so easily for others. There would be no remedy but a child. Why not help another couple expand their family? Why not help end the anguish? Why not “Pay it Forward” to the infertile community in such desperate need? The simplest answers to these questions became the best option.

So the decision came with three stages. Firstly, there was the genetic hurdle to consider. There is something about setting your genetic code, or more specifically, your potential genetic offspring, free into the world that can be somewhat unsettling. Where will these embryos end up, will they survive and what kind of life will they have? Will they know their history? Will they have questions? Will they look like me? But in the greater scheme of things, do these questions really matter?

The value and definition of family transcends any DNA makeup.

In the pursuit of the family unit, we tend to look beyond the genetic code and focus on the family element. The concept of having a family does not automatically equate to comparable genetic material as can be seen with any family with an adopted child. It’s about being part of a team, functioning as a whole and sharing your love and commitment to live and experience life together.

Secondly, there is an element of giving back; Paying it Forward to the infertile world. Donating the embryos was my way of paying back what I was so very fortunate to finally have – a family. Prominent memories of being unfulfilled without children are still fresh in my mind. I honestly believe that donating my idle embryos to someone in need helps to promote the probability of life.

And finally, chance. The chance to help someone build a family, the chance of potential life for the embryo, the  chance for you to give the greatest gift in life, the chance to take a chance! So for any of you out there who find yourselves with important decisions to make about your embryos in storage, think back a bit to your own infertile days. That memory will help guide you to do the right thing for someone with the same needs and desires as you have. Take a chance and do something good for humanity.

chance for you to give the greatest gift in life, the chance to take a chance! So for any of you out there who find yourselves with important decisions to make about your embryos in storage, think back a bit to your own infertile days. That memory will help guide you to do the right thing for someone with the same needs and desires as you have. Take a chance and do something good for humanity.

Donating the embryos was my way of paying back what I was so very fortunate to finally have – a family.

In the end I trusted Embryo Donation International (EDI) and Dr. Sweet with my precious embryos. I knew that with their high ethical standards and sheer devotion to the embryo they would give my embryos a chance at life, and hopefully help to build another family, just like they helped to build mine. And on every Mother’s Day ever since the donation I hope and wonder that by liberating my embryos they were able to help create another family somewhere out there and that they are as happy as I am.

Vicki D.

Mom, a Loving Wife and now, an Embryo Donor

torig71@gmail.com

Federal Funding of Embryo Donation and “Embryo Adoption:” Is it time for the Federal Government to Reconsider Its goals?

By: Craig R. Sweet, M.D.

Reproductive Endocrinologist

Info@EmbryoDonation.com

The “Defunding” of a Government-Supported Program

On March 2, 2012, it was reported that the Obama Administration wanted to defund the embryo donation/adoption awareness federal program that has been run by the Office of Population Affairs, part of  the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Spokespeople from Nightlight Christian Adoptions, the National Embryo Donation Center and Snowflakes Embryo Adoption programs were quoted as opposing the defunding decision. It should be noted they all had received or were receiving funding from the federal program, so their reactions were not unexpected.

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Spokespeople from Nightlight Christian Adoptions, the National Embryo Donation Center and Snowflakes Embryo Adoption programs were quoted as opposing the defunding decision. It should be noted they all had received or were receiving funding from the federal program, so their reactions were not unexpected.

Initially, the federal program was created in response to President Bush’s push to use cryopreserved embryos to create families and steer away donations from human embryonic stem cell research. Since 2002, over 22 million dollars has been spent by the federal government on the awareness programs.

The Predictable Response

Certainly during an election year, the firestorm that followed was probably predictable.

There were calls stating that the Obama Administration was “pro-abortion,”

I’ve never met such a person in my entire life, although many have been “pro-choice.”

Congressman Chris Smith, a New Jersey Republican, was quoted a saying, “Assertions that leftover embryos are better off dead so that their stem cells can be derived is dehumanizing and cheapens human life.”

Come on now… this decision does not mean that all cryopreserved will be destroyed. It simply means that all of us who are dedicated to the concept of embryo donation need to work harder and smarter with non-federal funds to make certain patients are aware of the embryo donation option.

Mailee Smith, staff counsel at the “pro-life” Americans United for Life, was quoted, “What we’re seeing is the elimination of the moral solution.”

Nothing could be further from the truth. Many programs throughout the country offer embryo donation and will continue to do so long after federal funding disappears.

Could we all just trim the hyperbole a bit?

Is it a Coincidence that the Phrase “Embryo Adoption” Predated the Personhood Amendments?

I suggest paying less attention to the hype and instead examine the realities of the ways that federal funding can influence the competitive free market with unintended consequences. The propagation of the term “embryo adoption” sprouted the appearance of the personhood amendments and legislation, which are focused on declaring that eight-cell early embryos are people. The consequences of these enactments are far reaching, including monumental legislative changes, restrictions on the care of women, and severe restrictions to the treatment of the infertile patient. (See my previous blog on the Mississippi Amendment here.)

Not Sour Grapes but Concerns Regarding Discrimination

Let it be understood that Embryo Donation International (EDI) applied last year for the federal funding in question, but we were not awarded a grant. In partnership with professors at Florida Gulf Coast University, we proposed thirteen different fresh and innovative projects to increase awareness, as well as provide embryo donation services. While we were disappointed, we were not surprised that the organizations, for the most part, receiving funding had been granted it before and this was our first submission. EDI was not previously dependent on the funding so there were no significant changes in our day-to-day operations. The projects are slowly being rolled out, funded instead by SRMS/EDI.

What bothered us was that over the years some of the organizations receiving the bulk of the funding were faith-based and discriminated against some patients. While the projects themselves were potentially more neutral, the organizations were not. Health and Human Services (HHS) apparently looked only at the proposals in determining the awards, making the awarding of grants potentially flawed.

The grant process essentially compartmentalized the proposals. If an organization provided certain services, which the federal government did not fund directly, but the organization was awarded a grant to provide other services, the government essentially compartmentalized the grant money separate from the procedures it didn’t directly support. I understand the concept but do not feel the grant committees should have made the decision based only on the grant proposals. They also needed to take into account the overall views and beliefs of the organization requesting funding. There needs to be times when the government must look at the trees and not just the leaves.

I believe there were instances where the funds should be withheld. The funded organizations should have provided a minimum standard of practice guidelines in line with the non-discrimination clauses outlined in the grants. Entities awarded the grants should not have discriminated with regards to race, religion, ancestry, gender, marital status or sexual preference.

Being a faith-based embryo donation/embryo adoption organization also directly or indirectly excludes some patients, making it uncertain if the federal government should directly support such facilities, especially taking into account the separation of church and state. I know that faith-based embryo donation/embryo adoption entities were strongly supported by past administrations but should a neutral organization that does not discriminate and makes all faiths feel totally welcome be placed at a higher priority now? Is this more ethical and fair? Is this a better use of the shrinking tax dollars? Is it time for the federal government to reconsider their goals?

Being a faith-based embryo donation/embryo adoption organization also directly or indirectly excludes some patients, making it uncertain if the federal government should directly support such facilities, especially taking into account the separation of church and state. I know that faith-based embryo donation/embryo adoption entities were strongly supported by past administrations but should a neutral organization that does not discriminate and makes all faiths feel totally welcome be placed at a higher priority now? Is this more ethical and fair? Is this a better use of the shrinking tax dollars? Is it time for the federal government to reconsider their goals?

If both discrimination and faith-based issues were actually taken into account, many of the organizations discussed here never would have received the original federal funds.

It is not that I want these organizations to go away. Quite the contrary, they often do a great job, provide excellent services and fill a much-needed niche. Their funding should, however, be through sources other than the federal government because of the bias inherent to their provision of services.

Can the Government Afford Providing the Grants?

Understanding that the U.S. is running a severe deficit, when are we ever going to be  willing to make difficult decisions? How are we ever going to get control of the budget if we can’t trim existing programs that may serve an important few when the many need assistance? We all need to look at the big picture and understand that “business as usual” is not practical in the current economic climate. I may be falling on the sword a bit, but shouldn’t we all be willing to sacrifice? Hey, I’m all for creating little taxpayers to help pay off the deficit. I’m just not sure that we can afford to do so through a government in the red. To do so with organizations that discriminate makes absolutely no sense at all.

willing to make difficult decisions? How are we ever going to get control of the budget if we can’t trim existing programs that may serve an important few when the many need assistance? We all need to look at the big picture and understand that “business as usual” is not practical in the current economic climate. I may be falling on the sword a bit, but shouldn’t we all be willing to sacrifice? Hey, I’m all for creating little taxpayers to help pay off the deficit. I’m just not sure that we can afford to do so through a government in the red. To do so with organizations that discriminate makes absolutely no sense at all.

In Summary

If federal funding is to continue, it needs to be provided to organizations, and not necessarily my own, which do not discriminate and are not faith-based. In addition, giving “embryo adoption” programs federal funds so they can support personhood amendments should be reconsidered. Having the government eventually spend even more money and time contesting the amendments and statutes in court defies understanding. Perhaps the congressional appropriations committees, who will make the final decision regarding federal funding, will take the concepts of non-discrimination and non faith-based alternatives into account and fund the programs with new and fairer goals.

Rest assured, unlike the rhetoric would lead one to believe, embryo donation is here to stay, regardless of the decisions of Congress and the grant process. How do we know? We’ve been providing the service for 11 years and will continue to do so in the years ahead, without cessation, as long as there are cryopreserved embryos available to donate.

Craig R. Sweet, M.D.

Reproductive Endocrinologist

Embryo Donation International

www.EmbryoDonation.com

Final Post in Mini-Series: Thawing/Warming Embryos

In the first two segments of this series, we discussed embryo grading and cryopreservation (1 – Do these embryos make the grade? and 2 – Embryo Cryopreservation: An Easy to Understand Review). This final segment in the series will examine the process of thawing or warming of embryos for transfer.

In the first two segments of this series, we discussed embryo grading and cryopreservation (1 – Do these embryos make the grade? and 2 – Embryo Cryopreservation: An Easy to Understand Review). This final segment in the series will examine the process of thawing or warming of embryos for transfer.

In Review…

Let’s begin with a short review of the previous blogs. You will recall that we discussed two methods of embryo cryopreservation, slow freezing and vitrification. Both methods require that the cells of the embryo have as much water removed as possible and that cryoprotectants, materials that protect the cells during freezing, be forced into those cells to reduce ice crystal formation. Slow freezing uses a controlled rate freezing instrument that slowly lowers the temperature to well below freezing to avoid the formation of ice crystals. Vitrification is a method in which embryos are plunged directly into liquid nitrogen and immediately turned into a glass-like substance, essentially cooling the embryos so quickly that ice crystals do not even have time to form.

Cryopreservation Storage Containers

One topic not covered in the freezing blog was the type of containers used to hold the embryos. Slow freezing, in most cases, uses straws or vials to hold the embryos in a small amount of solution called media. Vitrification uses many different storage devices to hold the tiny embryos, which cannot be seen without a microscope. These devices commonly include various types of straws, nylon loops or electron microscope grids, just to name a few.

How Often do the Cryopreserved Embryos Survive?

It is expected that about two-thirds of embryos cryopreserved via a slow freeze technique will survive thawing (Son and Tan, 2009) and the embryos that do not survive are most likely genetically abnormal. For embryos that are vitrified, the rapid cooling/warming process seems to work better, with about 80-90% of the embryos surviving. For this reason, vitrification is becoming more popular for cryopreserving both eggs and embryos.

How Many Embryos Should Be in Each Container?

Ideally only one or two embryos should be packed into each storage container. By packaging one embryo per container, the embryologist can thaw or warm only the exact number of embryos to be transferred without having any left over. For example, if a patient wants to have two thawed cryopreserved embryos transferred and they have a total of five embryos each frozen in separate containers, the embryologist will thaw/warm one container at a time until just two healthy embryos are recovered. If, however, the same five embryos were packaged in two containers with three embryos in one and two in another, the embryologist would probably first begin thawing/warming the container with three embryos. Should all of the embryos survive, there is one excess embryo that would need to be transferred, refrozen or discarded. While recent studies have indicated that freezing embryos a second time can result in a pregnancy, particularly when using vitrification, it is ideal to only thaw the exact number of embryos that we want to transfer and not one embryo more. (Kamasko, Y. et.al., 2009).

How are the Embryos Thawed/Warmed?

Ice crystal formation is also the enemy when thawing embryos, just as when cryopreserving them,. As embryos warm from -196°C (-321°F) toward 0°C (32°F), ice crystals may again form and damage the cells. We use the following techniques to rapidly warm/thaw both slow frozen and vitrified embryos in an attempt to avoid ice crystal formation:

- For embryos frozen by the slow freeze method, the straws or vials are removed from the storage tank and held at room temperature for 30-60 seconds, allowing the embryos to warm only slightly. The storage container is then plunged into 37°C water, completing the thawing process quickly enough so that the ice crystals don’t have a chance to form.

- Vitrified embryos are taken out of liquid nitrogen, with the container then plunged directly into warming media that is either at room temperature or 37°C, depending on the method used to vitrify the embryos. Once again, the ice crystals simply do not have enough time to form.

Once the embryos have been thawed/warmed, the cryoprotectants that replaced the water in the cells must be removed and balanced solutions placed back into the cells. To accomplish this, embryos are moved from small bath to small bath with varying concentrations of water and other substances. As the cryoprotectants are removed, the cells fill with water containing the nutrients and growth factors needed for cellular recovery. Once the embryos have been thawed/warmed, they are placed in the incubator in supporting culture media for two to twelve hours to allow the cells to continue equilibration prior to transfer. If we are thawing embryos that were frozen early, we may even grow the embryos for a few days so that we transfer the fewest healthy embryos we need to achieve a successful pregnancy.

Are There Other Factors That Influence the Survival of Cryopreserved Embryos?

While ice crystals play a big role in the survival of embryos, they are far from the only concern. Embryo survival rates vary for many reasons including;

- Embryo quality: Poor quality embryos freeze and thaw poorly. Poor early development of an embryo suggests that the embryo is in the process of dying and such embryos should probably not be cryopreserved.

- Freezing media and cryoprotectant “recipes“: Some recipes are potentially better than others and each laboratory has to find which works best. What works well for one, may not be the best for others.

- Laboratory techniques: Laboratories must have an excellent quality control program to assure they are following the steps involved in freezing/cooling and thawing/warming the cryopreserved embryos precisely.

- Embryologist variability: As with all techniques that involve humans, some seem to do a better job than others. There is no substitution for careful training and experience.

In Closing…

We hope this series has given you a glimpse of what is involved in grading, freezing/cooling and thawing/warming your precious embryos. Cryopreserved embryos give patients the option to build their families in a cost effective manner. Without cryopreservation, embryo donation would really not be possible.

Corey Burke, B.S, C.L.S.

Laboratory Supervisor

Embryo Donation International

CBurke@EmbryoDonation.com

References:

Kamasko, Y. et.al. The efficacy of the transfer of twice frozen-thawed embryos with the vitrification method. Fertil Steril 2009;91:383-386.

Son, W.Y., and Tan, S.L. Comparison between slow freezing and vitrification for human embryos. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2009:6(1),1-7

Embryo Cryopreservation: An easy to understand review

Why are Embryos Cryopreserved?

Infertility patients invest so much time, effort, money and emotion into each IVF cycle. After the fresh embryos are transferred, about 30-40% of our patients will have excess high quality embryos available for freezing, also known as cryopreservation, to be used for future cycles. Frozen embryo transfers are a cost-effective way to pursue further treatment, regardless of the outcome of the fresh embryo transfer cycle.

Patients are often curious about the methods their laboratory uses to freeze their embryos. Cryopreservation is a delicate process requiring extensive expertise to prevent damage to the embryos during the freezing and thawing procedures.

Preventing Potential Damage During Freezing

There are three major types of injury that can occur to cells during the cryopreservation procedure (Jain JK, et al., 2006):

- (i) Exposure of cells to ice crystal formation during freezing and/or thawing;

- (ii) Damage to the embryos from the solutions used to prepare the embryos prior to freezing; and

- (iii) Damage to the embryos as water and electrolytes shift in and out of the cells that make up the embryos.

Damage from ice crystal formation is overcome by removing as much water from within the cells making up the early embryo and replacing it with fluid containing cryoprotectants. To remove the water, embryos are placed in a series of solutions using increasing concentrations of salt to draw the water out of the cells. Once this is accomplished, the embryos are then placed into additional solutions containing the cryoprotectants, which enter the cells taking the place of the water.

Removing the water from the cells is relatively simple while replacing the fluids with cryoprotectants is a bit more difficult and damage to the embryos can occur if not done correctly. Cryoprotectants can be toxic to the embryos, so the cells can only be exposed to them for a very short time before they are frozen. Once the cells have been filled with cryoprotectants, cryopreservation needs to take place fairly rapidly.

Slow Freezing and Vitrification Techniques

The two most common cryopreservation methods used to freeze embryos are slow freezing and vitrification. The slow

freezing method has been around for decades. Slow freezing involves loading the embryos into special straws or vials and placing them in a separate container, which is surrounded by a liquid nitrogen bath. The container controls the rate of temperature drop and freezes the embryos slowly over a few hours, preventing most ice crystal formation. The freezing device lowers the temperature gradually to -38° C. Once the embryos have reached this temperature, the vial or straw is plunged into a bath of liquid nitrogen to reach a final temperature -196°C (-321°F). They will remain at this temperature until they are thawed.

With vitrification, embryos are rapidly cooled to -196°C (-321°F) almost instantly. This instant cooling does not allow ice crystals to form. Vitrification comes from the Latin vitreum, meaning the transformation of a substance to glass. Please note the use of the word “cooling” is used rather than “freezing” when referring to vitrification. Freezing actually involves transitioning a liquid to a solid through crystallization. No crystals are actually formed during vitrification. To understand the difference better, take a look at an ice cube from your freezer. While it is mostly clear, you will notice it is somewhat cloudy due to ice crystal formation and not as clear as glass. Water that is vitrified appears absolutely clear because ice crystals never had the chance to form and a glass-like substance is created.

Vitrification still requires the replacement of water with cryoprotectants but uses a different recipe. In fact, the cryoprotectants used for vitrification are at a higher concentration and potentially even more toxic to the embryos. Once the embryos are exposed to the high concentration cryoprotectants, they must be frozen very rapidly. Whereas the slow freeze process takes place over hours, vitrification takes place over minutes.

Is One Cryopreservation Technique Better than the Next?

The process of embryo vitrification is relatively new compared to the slow freeze method; however, great advances have been made over the past decade.

There is evidence that vitrification is a slightly better system than slow freezing. In most studies, the embryo survival rates are better for vitrification than the slow freeze technique. A recent study by Kaskar, K. et.al, also showed that the pregnancy rates with vitrified/warmed embryos (64%) were significantly higher than those that were frozen/thawed by the slow freeze techniques (47%). With higher survival rates and higher implantation rates, vitrification is slowly replacing the slow freeze technique, especially for the storage of eggs and embryos.

Success with Re-vitrification

Vitrification may allow embryos to be warmed, re-vitrified, and warmed again with successful pregnancies reported. While the pregnancy rates are somewhat lower that that of embryos vitrified only once, the results are far better than embryos slow frozen, thawed, re-frozen, and thawed yet again. A 2007 study by Kamasko, Y. et.al, showed no significant differences in implantation rates between once vitrified embryos and twice vitrified embryos. The reason this is important is that embryos may be frozen/cooled in groups larger than we want to transfer. For example, if a patient succeeded with a twin pregnancy with two fresh embryos transferred and only wants one frozen embryo transferred for a future child, having two cryopreserved embryos survive that were stored in a single vial would present a problem. In this case, we would possibly transfer more embryos than we wanted to, discard the extra embryo (not at all desired) or refreeze/re-vitrify the extra embryo. Using vitrification, the embryo may indeed survive a second stage of warming for an additional pregnancy in the future.

Your Embryos Are Very Important

As embryologists, we take our responsibilities to care for your cryopreserved embryos very seriously so that you will have the opportunity to use them for future treatment cycles. Rest assured they will be available when you need them, having been cryopreserved with the most state-of-the-art techniques at our disposal.

Thawing/Warming Your Embryos

If you would like to learn about how embryos are thawed/warmed, be sure to watch for our upcoming blog on this topic!

References:

Kaskar, K., et.al. Comparison of clinical outcome of blasocyst vitrification with slow freezing and fresh embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 2010;94:113-114Jain JK, Paulson RJ. Oocyte cryopreservation. Fertil Steril 2006;86(Suppl 3):1037-46.

Kamasko, Y. et.al. The efficacy of the transfer of twice frozen-thawed embryos with the vitrification method. Fertil Steril 2009;91:383-386

Do These Donated Embryos Make the Grade?

Embryo Grading Made Easy For Embryo Donors and Embryo Recipients

Part 1 of a 3 part mini-series by Corey Burke, B.S., C.L.S. & Laboratory Supervisor and Reproductive Endocrinologist Craig R. Sweet, M.D.

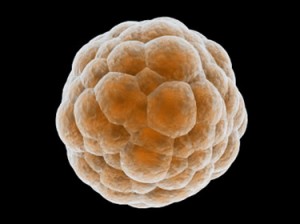

Embryo grading is an important factor for both donors and recipients. Potential embryo donors want to know if we will accept their embryos for donation since part of our decision is based on the grade of their embryos. Likewise, potential embryo recipients want to know how likely the donated embryos are to survive thawing and if they are of good enough quality to build their family. Part of our estimation of success depends on the grade of the embryos.

We wish this process could be easier since there is no standardized system used in all embryology laboratories to grade embryos. Furthermore, the grading of embryos is somewhat subjective so one embryologist may grade an embryo

somewhat differently than a colleague.

Embryo grading is an imperfect process; poorly graded embryos may occasionally result in ongoing pregnancies and beautiful looking embryos may not implant and grow. Poorer graded embryos will not necessarily result in an abnormal child; they simply seem to implant and grow less frequently.

So, the appearance and grading of an embryo is an imperfect estimate of the quality of the embryo as well as the embryo’s true potential. It is, however, the best way we have to visually estimate the implantation and live birth rate of a given embryo. We will now examine one of the more common methods used to grade embryos.

When are embryos graded and cryopreserved?

Embryos are usually graded and frozen at three specific stages with “Day 0” being the day of retrieval and fertilization:

| Age of Embryos | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5-6 |

| Common terminology | 2PN (pronuclear stage)

2 cell stage |

Embryos are 6-10 cells | Morula &

Blastocysts |

| Grading importance | Grading not available | Grading relatively important | Grading very important |

| How often these are sent to EDI? | Rarely sent | 40% of EDI embryos | 60% of embryos |

Embryos cryopreserved immediately after fertilization are confirmed early on Day 1 (the 2PN (pronuclear stage), but aren’t advanced enough to be consistently graded. Freezing embryos on Day 1 is quite infrequent unless we are certain there will not be an embryo transfer. Accordingly, these embryos are rarely sent to EDI for embryo donation.

Grading Day 3 Embryos

Day 3 embryos are graded on cell number, the amount of cellular fragmentation and the symmetry of the embryo.

Cell Number

Most Day 3 embryos will be comprised of 6-10 cells called blastomeres. Embryos with too few blastomeres may not be healthy, so we prefer at least 7-8 at this stage. Embryos with fewer cells may not be healthy growing very slowly or may have stopped growing entirely commonly called “cell block”.

Fragmentation

Fragments may be found in many of the embryos, which are “bits” of cells that break off from a blastomere. We prefer as little fragmentation as possible. Fragmentation is estimated as the percentage of fragmentation volume compared to the total embryo volume and is converted to a letter grade in the following way:

- 0 % = A

- 1-10% = B

- 11-25% = C

- >25% = D

A large amount of fragmentation may be caused by death of one or more of the blastomeres. The higher the fragmentation, the lower the quality of the embryo & letter grade and the less likely that the embryos will survive thawing. Embryos with high fragmentation rates implant less frequently when transferred fresh or when thawed.

Symmetry

Symmetry of the embryo refers to the shape of the individual blastomeres and the overall shape of the embryo. The blastomeres should all be very similar in size and generally round in shape. The scale used to grade symmetry is

- Perfect = A

- Moderately asymmetric = B

- Severely asymmetric = C

Severe blastomere asymmetry (i.e., large and small blastomeres in the same embryo) reflect nuclear/chromosomal and cytoplasmic problems suggesting the embryo is less healthy than desired. There is supporting evidence that blastomere symmetry is important and reflects overall health of the embryo. Interestingly, the overall symmetry of the embryo (round vs. oval) is of uncertain importance with some very “funny looking” embryos resulting in beautiful and healthy children.

Putting it All Together for Day 3 Embryos

For Day 3 embryos, the order of grading is the “number of cells (#c),” “fragmentation grade” and “symmetry grade”. For example:

- 7cAA = 7 cells with no significant fragmentation and perfect symmetry

- 8cBA = 8 cells with 1-10% fragmentation and perfect symmetry

- 6cBB = 6 cells with 1-10% fragmentation and moderate asymmetry.

Grading Day 5 Embryos

More advanced embryos are graded and potentially frozen on Day 5 or Day 6. These are generally described as morula or blastocysts.

Day 5 Morula Embryos

Morula embryos are difficult to grade as the cells combine, forming essentially a ball of cells that can’t really be categorized in any way other than descriptive terms:

- Morula (early)

- Compacting morula (more advanced)

While some facilities only occasionally cryopreserve Day 5 morula embryos, it is thought that the survival and implantation rates of these embryos may be slightly reduced but they are still quite reasonable, suggesting that they should not be discarded. Day 6 morulas are probably delayed in growth or may have stopped growing, may not be viable and are infrequently cryopreserved.

In order to balance the possible reduced implantation rates, it is common that more morula embryos are thawed and transferred in order to achieve success.

Day 5 Blastocyst Embryos

Day 5 blastocyst embryos are the most advanced embryos we see in IVF. These embryos are formed within 24 hour of actual implantation. Trying to grow embryos beyond this point is

technically difficult, as the embryos usually don’t survive. In addition, the window of time for implantation seemingly closes beyond Day 5 or early day 6. For example, transfer on Day 7 will rarely result in implantation. So, it simply makes more sense to transfer and/or freeze blastocysts rather than trying to grow them any further.

Along with descriptive measures, more objective grading is attempted through evaluation of the cellular expansion, the inner cell mass (which eventually becomes the fetus) and the quality of the outer cell mass called the trophectoderm (which eventually forms the membranes and placenta).

Expansion

As the embryo advances in growth, a cavity called the blastocoel fills with fluid. As the cells continue to divide and the fluid collects, the embryo expands and eventually escapes its outer covering called the zona pellucida. The blastomeres continue to group together wherein the individual cell cannot be counted. As the Day 5 embryo expands, differentiates and escapes the outer zona pellucida, the grade increases numerically from 1-5.

| Grade | Description | Physiology |

| 1 | Early Blastocyst | Starting to form a fluid-filled space in the middle (Blastocoel). Grading the embryo is difficult here. |

| 2 | Full Blastocyst | Blastocoel forms and inner cell mass is now distinguishable. Grading can be done from this point forward. |

| 3 | Expanded Blastocyst | Blastocyst is starting to expand in size thinning the outer covering, the zona pellucida |

| 4 | Hatching Blastocyst | Blastocyst is starting to hatch out of the zona pellucida. |

| 5 | Hatched Blastocyst | Blastocyst is fully hatched and now ready for implantation into the uterine wall. |

Inner Cell Mass (ICM)

As the blastomeres compact to form the inner cell mass (ICM), this early fetal tissue is graded on a A-D scale:

| ICM Grade | Description |

| A | ICM with total compaction |

| B | ICM still compacting |

| C | Reduced ICM |

| D | Poor with dying cells |

Trophectoderm (TE)

The outer cells of the trophectoderm (TE) also reflect the overall health of the embryo and are graded in an A-D scale.

| TE Grade | Description |

| A | Numerous cells forming cohesive layer |

| B | Few but healthy large cells forming a loose epithelium |

| C | Few cells present often with asymmetric distribution |

| D | Poor with degenerating/dying cells |

Putting it All Together for Day 5 Embryos

For Day 5 embryos, the order of grading is “expansion,” “inner cell mass” and “trophectoderm.” For example:

- 1 = Early blastocyst is unable to be easily graded with respect to ICM or TE as these haven’t separated well enough yet.

- 2BB = Blastocyst with partial ICM compaction with loose, large trophectoderm cells

- 3AB = Expanding blastocyst with total compaction of ICM and with loose, large trophectoderm cells

- 4AA = Hatching blastocyst with excellent ICM & trophectoderm cell layers

- 5AA = Fully hatched blastocyst with excellent ICM & trophectoderm cell layers

Day 5 embryos that are graded 4AA and 5AA are some of our favorite embryos.

Summary Comments

Embryology laboratories strive to grow the healthiest embryos they can. Over time, they have adapted different grading techniques so the laboratories can communicate the quality of the embryos to physicians, patients and each other. Not all beautiful embryos will implant or produce a healthy child but they seem to do so more often than others. Not all poorly developing embryos will fail to implant and produce a healthy child but most do not result in live offspring.

At EDI, we try to only accept embryos that are likely to implant so embryos with less than a B rating for any category are infrequently accepted. This is done to assure our recipients that all of the donated embryos we offer are of the highest quality and provided the greatest chance for a successful pregnancy.

This is only one piece of the puzzle as many other factors influence the likelihood for success. Dr. Sweet will cover this topic in the separate blog within the next couple of months.

Also stay tuned to the upcoming blogs regarding how embryos are frozen and thawed and what techniques seem to work the best.

While embryo grading is not a perfect system, we use it to try to predict the overall quality of the embryos and their potential to survive thaw, grow and build a recipient’s family.

Corey Burke. B.S., C.L.S.

Laboratory Supervisor

CBurke@EmbryoDonation.com

Craig R. Sweet, M.D.

Reproductive Endocrinologist

Info@EmbryoDonation.com

References

Racowsky C, Vernon M, Mayer J, Ball GD, Behr B, Pomeroy KO, Wininger D, Gibbons W, Conaghan J, Stern JE. Standardization of grading embryo morphology. Fertil Steril. 2010 Aug;94(3):1152-3.

Are Open Embryo Donation Procedures Better Than Anonymous?

Gamete donation of sperm, eggs or embryos has been occurring for quite some time. Sperm donation probably occurred as far back as 1884 in the US (Wikipedia, 2011). Embryo donation was first reported in Australia in 1983 using both fresh and frozen embryos. (Trounson A, Mohr L, 1983). Egg donation probably first took place in the U.S. in 1984 around the same time as the first embryo donation procedure (Blakeslee S, 1984).

Gamete donation of sperm, eggs or embryos has been occurring for quite some time. Sperm donation probably occurred as far back as 1884 in the US (Wikipedia, 2011). Embryo donation was first reported in Australia in 1983 using both fresh and frozen embryos. (Trounson A, Mohr L, 1983). Egg donation probably first took place in the U.S. in 1984 around the same time as the first embryo donation procedure (Blakeslee S, 1984).

Certainly in the early years of sperm/egg/embryo donation, the procedures were almost always done anonymously. Designated donations also took place using family and friends but they were the exception rather than the rule. Having donors and recipients meet was not really an option in the past.

Is non-anonymous sperm/egg/embryo donation becoming more common?

Over the years, there has been movement towards non-anonymous or known donations. Countries such as Sweden, Norway, Netherlands, Great Britain, Switzerland, Australia and New Zealand only allow non-anonymous sperm donations. In a future blog, we will cover some of the consequences that occur when countries completely move from anonymous to non-anonymous donation procedures. At least in the U.S., there is a choice, though Washington State recently passed legislation that makes it more difficult for anonymous sperm and egg donation to take place. I will discuss this legislation and topic in a future blog since this is an important and concerning development. An increasing number of donor sperm and donor egg banks offer non-anonymous donation, although, with rare exceptions, this remains a minority of the procedures performed in the U.S. (personal communication).

Does EDI offer non-anonymous embryo donation?

At Embryo Donation International, we offer Open Embryo Donation where the donors and recipients have the ability to communicate, meet and establish a relationship. Other facilities tend to call it “embryo adoption”, a term we are at odds with (click here for more information), where there is an attempt to foster relationships. Interestingly, at EDI, this is rarely requested although we feel it appropriate to offer such an alternative.

If embryo donors & recipients meet, what is the outcome?

If families do connect, there are a number of relationships that need to be considered. The first involves the donor(s) and the recipient(s). No one knows if these relationships will last. Romanticizing the idea of everyone being one happy family may be misguided. There are certainly examples where friendships have developed, such as the families profiled this Good Housekeeping article, but the number of relationships that don’t flourish are simply unknown. We all have to go through so many acquaintances to eventually find our true friends, so it remains uncertain if these initially awkward relationships will last beyond the transfer process. Long-term studies are lacking.

The second relationship to be considered would be with the resulting donor offspring and the donor(s). In an Open Embryo Donation procedure, the child will not only know the genetic and family history in detail but they will most likely know the names of the donor(s). The likelihood of this child trying to eventually connect with the donors is great. While there is a genetic bond, it remains uncertain if the relationship will always be welcome or beneficial. Certainly in the adoption world, adoptees that eventually find their family are not always rewarded with utter acceptance and may experience rejection, as they see it, a second time. Once again, long-term studies are lacking about the effects of an open embryo donation process with regards to the potential relationships between the donors and the donor offspring.

Lastly, there are the potential relationships between the siblings created when the donor has children of their own or donates to other recipients with offspring created. These children share a solid genetic bond and may feel rewarded in forming a relationship with their genetic brothers and sisters. Only careful, long-term and unbiased research will be able to identify the outcomes of such relationships. My best estimate is that these relationships may be sustainable but what will happen if the donor offspring are not fully accepted by the donors or the donors and recipients are no longer close?

Will my doctor be able to help me with my decision to have an open embryo donation?

So, would you want to meet your donor? Would you want to meet your recipient? It would be ideal if your clinician could clearly guide you as to the expected outcome of an open process. In reality, we are also diving into the thorny question regarding disclosure of one’s origins to embryo donor offspring, something that I will be touching upon in the months to come. For now, however, I suggest a point of caution. The world of embryo donation is simply not the same as the world of adoption and extrapolating one to the other is not without risk.

The issues we are discussing involve currently unknown long-term consequences and we need to be careful, thoughtful and unbiased in recommending one embryo donation procedure over another. For now, I believe it is a very personal decision that only embryo donors and recipients can make based on how they currently feel and what they believe will happen in the future.

I hope that we physicians deeply involved in the world of embryo donation will better be able to discuss the long-term advantages and disadvantages of open vs. anonymous procedures, but for now, the patients will simply have to guide us.

References:

“Sperm Donation.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 23 July 2011. Web. 24 July 2011. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sperm_donation.

Trounson A, Mohr L. Human pregnancy following cryopreservation, thawing and transfer of an eight-cell embryo. Nature 1983;305:707-9.

Blakeslee, Sandra (1984-02-04). “Infertile Woman Has Baby Through Embryo Transfer”. The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research – Reimbursement Debate

Should Patients be Reimbursed for Donating Their Embryos for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research?

By Dr. Craig R. Sweet

Medical & Practice Director

Founder, Embryo Donation International

Introduction:

There are a handful of academic and private research facilities in the U.S. performing human embryonic stem cell (hESC) research. The use of embryos for research is an emotionally charged issue, with prolife and prochoice proponents having opposite viewpoints. The advantages and disadvantages of the research are not the focus of this discussion. EDI feels this is a very personal choice, which only should be made with great care and thought.

Let us assume for now, and at the risk of offending some, that there is potential merit to hESC research.

Most Donors Change Their Minds

Approximately 71% of the patients who state they will donate their unused embryos routinely change their minds, with most discarding them instead (Klock SC, et al. 2001). In fact, only about 5-10% of the patients actually donated their unused embryos for hESC research (Elford K, et al. 2004 & Klock SC, et al. 2001). Why do so many change their minds?

Would the percentage of embryos donated for research increase if donors were given a minimum level of financial reimbursement?

Inappropriate Enticement?

Centers performing hESC research are under very strict guidelines. Institutional review boards for human experimentation, which oversee such studies, forbid any level of coercion in obtaining embryos. Coercion can mean many things, including offering excessive financial incentives. But in my opinion, restricting even small tokens of appreciation can be counterproductive. For example, when we worked with Harvard’s hESC lab, we wanted to offer patients a $25 gift card to encourage them to complete the paperwork within 30 days so we could transport the embryos to the study facility as quickly as possible. Soon after starting this, we were told to stop because even a $25 gift card might be interpreted as inappropriate enticement.

Does anyone really think the $25 would inappropriately convince a patient to

donate their embryos for hESC research when they would otherwise not have done so?

In a pilot study performed by our parent organization, Specialists In Reproductive Medicine & Surgery (SRMS), we found the average cost per embryo transferred or cryopreserved was $2,400. This study included patients with and without insurance coverage. These estimates didn’t include the costs of time away from work, pain, suffering or any other infertility treatment expenses leading up to the IVF procedure. Interestingly, the cost per embryo transferred or cryopreserved ranged from $650 to $23,000.

What if the reimbursement was always far less than the amount that was spent to create the embryos, to make certain no one ever created embryos for profit?

Will Researchers Benefit?

Is there any doubt that academic centers and private companies may benefit from hESC research? If there is a scientific breakthrough at a hESC research facility, isn’t it reasonable that they will benefit from research dollars and/or actual profits? Even the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Council on Ethical and Judicial affairs states: “Profits from the commercial use of human tissue and its products may be shared with patients, in accordance with lawful contractual agreements.” (AMA, Opinion 2.08)

Is it wrong to ask why the patients who provided the embryos shouldn’t be reimbursed for even a fraction of what it took to create them?

What Do Patients Think?

In Netwon’s 2003 paper examining attitudes towards embryo donation procedures, 16% of those interviewed rejected embryo donation without some reimbursement with another 32% uncertain. (Newton CR, et al. 2003). This is compelling evidence that some patients felt the embryos had worth and that a level of reimbursement was not only desired, but required.

What Did You Think?

We conducted a poll on Facebook asking: “Should patients be compensated for donating their embryos for human embryonic stem cell research? Why or why not?” The following were the results:

- No: 11 people (69%)

- Uncertain: 2 (12%)

- Yes: 3 (19%)

While not a very large poll, the overriding opinion was no. I certainly respect their view. Clearly, reimbursement is not appropriate for all. I can’t help but wonder, however, if it would be appropriate for some.

I suggest that reimbursement for research studies is commonplace but seems to be forbidden in hESC research. What makes it so different? Facilities conducting this research are under a magnifying glass and most likely are afraid of criticism regarding human embryos. Are they afraid of a public relations backlash? Perhaps they truly feel it is ethically inappropriate, even though participants in other forms of clinical research; sperm, egg, and blood plasma donation; and surrogacy and adoption are reimbursed or compensatedfor reasonable and customary expenses and time and effort. But any suggestions about reimbursing for human embryos seem to be taboo.

Will Reimbursement Reduce the Number of Embryos Discarded?

So will adding a small financial incentive change human behavior and reduce the number of embryos discarded? Would a study exploring this clear institutional review board perusal for human experimentation oversight? Simply posing the question won’t work as people change their minds about embryo disposition. A randomized, multi-center longitudinal study might answer the question. In this study, some patients would be reimbursed and others not, with the number of embryos donated to patients in need or research would be compared to the number that were ultimately discarded.

Will anyone be brave enough to initiate such a study?

In Summary

What if a small amount of money was provided for embryos destined for hESC research? If reimbursement was provided, the research facility would need to require documentation of the money spent to create the embryos. It would be absolutely necessary that the facility always pay far less than it ever took to create the embryos. We must make certain that no one would ever create the embryos for profit, something I feel is overwhelmingly inappropriate.

Those who do not feel comfortable with reimbursement could simply refuse or request a donation be made to charity. Since we currently are forbidden to reimburse patients for embryos donated to patients in need at EDI, we instead donate to charity in either the donor’s name or anonymously. It is the best compromise we could find.